Hi Sandra,

Thanks for taking the time to write so clearly and thoroughly.

I did indeed misunderstand or at least not see the whole picture of your proposal before. I think you still do not see the big picture for crowdmatching. We’re not likely to drop crowdmatching and go with your proposal, but I like a lot about it and want to encourage you on this. The two approaches could co-exist (but not merge).

I can see how you’d want an institution with the mission and overall perspective that we have as the place for your overall good idea, and I think I understand why you have your bias against crowdmatching.

Meta comment: I am learning that in-line replying is not so good in this medium. A live conversation could go much better as a back-and-forth of that style (but it lacks the ability to think through and edit etc). I’d like to think about how to use this forum where we encourage short replies, wait for response, like a slow-motion live conversation…

I started replying-while-reading, but instead, here’s my new thoughts about it all:

Precise threshold overall

Your proposal is a fine enough system for what it is. It does address the snowdrift dilemma in terms of game-theory.

I’d characterize it as basically monthly-recurring-threshold-campaigns. Instead of the high costs of mounting a new, distinct Kickstarter every month, it’s recurring by design. It has mutual assurance from the threshold and sustainability (unlike any other system we know of aside from what we’re doing).

In the end, I think your proposal is actually great and is just a different model. It might work very well for smaller, niche projects that actually have a clear real threshold that isn’t just a guess at what will work with the game. For example, a minor fantasy author with a small but dedicated following who wants to just quit her day job. Both crowdmatching and precise-threshold are good systems that will work for different sets of projects that only partially overlap.

I actually think we should keep in touch and continue this discussion further. There’s a number of ways forward. We could have your system as another model (but that would have to be much later, can’t spread too thin at launch). You could take what you like about Snowdrift.coop and build a new platform for your approach. We could formally partner, integrate, but maintain separate systems…

On the differences between project fit

If you have in mind the prototypical best-fit for precise-threshold (ongoing, niche, knows what a good-enough salary is that would allow to quit a day job, is a make-or-break question for the project going ahead etc), then I can easily see how all the intuitions around that would lead to disliking crowdmatching.

Similarly, thinking of the prototypical best-fit projects for crowdmatching, precise-threshold seems bad. Right away, the first step “projects set a desired monthly income” being more than a general vague estimate but is an all-or-nothing threshold… that in itself already feels bad for the prototypical crowdmatching-best-fit project. And the idea that only optional tips will be encouraged beyond this is even worse.

So, I really think this is a matter of what sorts of projects fit each system. Which is to say, I think it might be best for both models to be available in some form. I’m also very happy about your consistent FLO public goods emphasis.

Someone could provide precise-threshold with too much proprietary crap and other stuff bad for the public interest… unlike crowdmatching, precise-threshold could make sense for even rivalrous goods. Precise-threshold could even work for a CSA farm, for example. Each new patron would reduce both the burden and the rewards for existing members. Subverting supply-and-demand, farmers need a certain salary; that salary is paid by any number of members as long as it gets paid; everyone gets their proportional share of the produce in the end. That’s a weird twist, but it should be obvious how crowdmatching couldn’t fit that case. That highlights some of the major differences.

Projects for precise-threshold

I could see some artists of various sorts, the type who don’t care to expand into broader things being good fit. Say a blogger who just wants to keep writing their essays, or a programmer who works on some quirky things that never need more than the one person, or a musician who has no ambitions beyond recording their music at home and publishing it online.

Those example all need enough reliable salary to feel safe quitting their day job. They appreciate tips. But they just want to do their work, get by well enough, and engage with their audiences.

Crowdmatching, even with a minimum threshold, makes little sense here. They can’t quit their dayjob until they have their threshold, and yes it feels weird and bad to punish (I’ll accept that term in this context!) the patrons by making them pay more just because the author is getting more popular. All your intuitions hold up in this context.

And yes, the single road snowdrift metaphor here applies well.

Projects for crowdmatching

Consider, for example, the real-world case of Task Coach, the initial motivation for crowdmatching. There were two volunteer developers and one volunteer support person (me). One dropped off. A few extra dollars are similar to a tip, it just helps cover costs and keep volunteers form burning out. But bigger budget is needed to get a part-time dedicated programmer or freelance help or even multiple full-time devs.

The project could certainly use a whole team, programmers, support people, marketing, user research, design specialists… So, while an amount that could fund a freelancer to spend 5 days a month would be definitely worthwhile, a funding of multiple full-time people would be even better. Small improvements would be nice, but the potential is much further.

Ideally, Task Coach would be ported to various contexts, web app version, mobile, etc. and eventually be able to out-compete all the proprietary task-management tools…

Precise-threshold here is not awful, but it’s not great. Should the threshold be the minimum get-a-freelancer-some level? The one-full-time level? Or…? As it gets more popular, we don’t want (neither the project nor the patrons) to have the funding level off. We want it to grow, add more to the team, prosper, become the wonderful, reliable tool we dream of…

Maybe this applies even more to something much larger like a major news organization. We want Common Dreams to grow to compete with the NYT. They need multiple journalists, editors, tech people… but just being able to have some extra funding to pay one more freelancer is still a good thing…

Crowdmatching in these cases mean that we do something positive but small in the beginning, and as we see progress and invite more people, we’re all thrilled to donate more to this thing that is on track to being the wonderful institution we dream of but still has a ways to go. Each extra set of pennies I put in are part of getting dramatic improvements over the next months… I’m not being punished, I’m taking an ever smaller portion of the burden as part of a growing community changing the world!

That whole dream of really building a better public goods economy and economic democracy feels hopeless with precise-threshold which is so modest and small scale and is only likely to have much impact in the aggregation of lots of little valuable niche projects.

Combinations / adaptations?

There may still be ways to adjust the numbers in crowdmatching or otherwise make more flexibility to broaden the set of projects that fit well. Similarly, there are surely ways to adapt precise-threshold.

And they could be combined still, even with “shares” or other approaches that might match efforts rather than number of patrons. Etc.

But we should be wary of complexity and muddling. So, I think at this point that having the two systems seem sensible. I really think the amount of non-overlapping projects (where one system is good and the other bad) is large enough that there’s real demand for both approaches.

(Side note: if Liberapay were more really strictly dedicated to public goods instead of sorta whatever-but-we-like-libre-stuff, I’d be that much more inclined to suggest you bring your idea to them. I would like to see your system available, especially in a way that lives up to ethical ideals.)

Some edited in-line replies for reference:

On game theory

Without going into details, you’ve discussed the game theory without adequate emphasis on the effects of iteration. But you’re mostly right about things by my reading overall.

a successful outcome every step of the way

The key point (made before) is that small donations from crowdmatching are positive not negative for a project that is going ahead no matter what. It’s better for the “suckers” who are clearing the road anyway to get some help and encouragement rather than to take on the costs of promoting a threshold campaign that doesn’t succeed and then be marked a “failure”. That mark is only good if the right thing is actually to give up (which it is, in some cases).

Joining in early and no-one else showed up? N.p. you’re not out anything. Joining in late and many others joined in? N.p. many hands made very light work.

Same in crowdmatching, since the amount you’re “out” when you’re early is small and is still something positive and you’re getting matched, so your pledge gets the project more than just your pennies.

where is the money coming from?

(all you say is right here)… the long-term goal is for the money to come from the pot going to proprietary stuff. We want people to stop funding Adobe and fund Inkscape instead. In essence, it’s the existence of robust proprietary stuff that proves we have the resources to make it, it’s just a matter of directing them to FLO public goods instead.

“Sorry, users can only put one image in a post.”

UGH! I plan to go through this thread with @Salt and fix things like this and then delete this meta comment.

Issues with your graphs

Besides not including crowdmatching + min. threshold option, there’s a major oversight: given people simply being aware that the road is now getting cleared enough, all of the graphs should taper off. Once good-enough funding happens, traditional subscribers stop joining, crowdmatching stops getting as many new pledges (especially since people are even more hesitant to accept the now-high pledge value), and plain threshold new pledges drop off too.

In short: accelerating beyond what’s valuable is a problem that is speculative and dubious. Nobody will pledge a $100/mo crowdmatching to a future Inkscape that is already so well funded, it does everything everyone wants. Regardless of any mechanism, it’s easy to just spread the concept that it’s fine to freeride for an already well-funded project.

(side-note: a popular author is more likely to get people just wanting to pledge anyway out of excitement versus something like Inkscape, so again, project-fit is relevant)

So, we predict a natural equilibrium with crowdmatching. It gets expensive, so people start dropping out, which itself reduces the crowdmatching. If too many patrons drop, it will go low enough that others feel fine joining and think it’s important for the project. The prediction with crowdmatching is that it will not overperform because of the natural behavior of patrons, no need for a precise threshold (but, as stated before, we could add a top threshold to crowdmatching if we’re wrong).

To most people, is it more appealing to be able to set your fixed monthly donation a la Patreon, or, to set a window within which your donation can jump around chaotically, a la crowdmatching?

People individually like the former. And it fails to fund public goods.

The point isn’t that people want to give up the control of setting their fixed monthly donation. The point is that patrons retaining that control is an obstacle to flexible negotiations. It’s similar to people wanting to freeride and have successful public goods. We’re saying, “sorry, if you want public goods, you have to accept the discomfort of giving up some control and focusing on working in solidarity with others — but we at least give you a hard budget so you can limit the risks until you feel comfortable raising that limit”.

Crowdmatching is not the natural thing everyone wants, it’s a cooperative negotiation we need to get at least partly over the freerider problem.

And while I think threshold systems in general are weak in these negotiations, I’m sympathetic to your suggestion that hiding the progress in precise-threshold is helpful. I totally see how that feature fits with the refund-past-threshold assurance to make the game-theory work far better than it does with a Kickstarter-style threshold!

But your take on crowdmatching is that your effort needs to match the amount of people making an effort, rather than their effort.

Hence the earlier “shares” formula. Matching efforts (instead of people) does make some sense, but makes everything far more complex (feedback loops even if the matching were designed wrong). So to be clear: my intuitions match yours, and we started with the effort-matching idea.

Over time, in negotiating with everyone involved and difference ideas, we moved to simplify the system (for now at least). You seem clear on our shared appreciation for maximizing the number of patrons as independent value from the total dollars. I won’t belabor that.

One anecdote though:

I was told by someone about a charity campaign that explicitly refused any donations over $25. That was interesting, why would they do that? All sorts of reasons, but it gets at this idea of focusing on inviting more people, knowing that you can’t just hope for a wealthy patron to come solve it, and people can’t feel guilty for not doing more etc. and the campaign was a great success (it was a medical thing, I think, like support for a child with cancer). I encourage you to reflect on that example.

As far as I understand it, crowdmatching has several mechanisms that work against maximizing the quantity of patrons.

like what? You mean like this next quote?

Also, with crowdmatching, you might not be able to afford pledging to a popular project, no matter how much you care about it.

…which is why the limits page offers ideas like sub-projects etc so if too-expensive is our problem, we do have ideas to address this.

With prec-shold, pledging late eases the burden of everyone else

And, again, speculative future but… we can do this with crowdmatching, as I’ve stated. I know that’s not your proposal, but it’s completely compatible. We can run a new engine the other way once a “fully-funded” threshold is hit. It would have the same effect whether we arrive at fully-funded via crowdmatching or not.

Instead, you want the maximum benefit (e.g. successful project) at minimum cost to you.

Yes, but it depends on the numbers of the benefit and the cost. The game plays differently if the benefits are minor and the costs are high versus the other way around. In crowdmatching for public goods, the costs of participating are not high (but are higher than the true minimum of freeriding), but the benefits are high (assuming valuable projects). And your pledge being matched means a greater increase in benefits than in costs.

Crowdmatching feels like patrons are being punished.

Besides my points above how this framing makes sense for some types of projects and not at all for others, there’s cultural context maybe:

If you live in a world of people who care about public goods and tend to be thoughtful etc., it’s easy to feel like crowdmatching is discouraging…

Out in the world of people who use Facebook all day, have never used an adblocker, think a just-world fallacy (that rich people deserve their wealth and vice versa) and buy into other corporate capitalist propaganda, they are still pro-social in a way (as healthy non-sociopaths are inherently), but they don’t contribute on Patreon or whatever, and they think the idea of FLO public goods is an absurd fantasy. They still think somehow that Wikipedia is just a bizarre anomaly rather than an example of what’s possible. Those people have their own biases, but they recognize correctly that the economics of FLO stuff are pathetically near-zero compared to everything else, and they see people like you and I as totally Quixotically delusional.

All the fuzzy stuff in between, there’s people who get that maybe FLO public goods aren’t hopeless but they sure seem that way, and they are already pretty damn discouraged. I know that feeling.

It’s a very uncomfortable thing to say, but we are actually self-aware guilty of basically going to the most optimistic, hard-working FLO activists who volunteer and donate now and are telling them: you live in a weird semi-delusional bubble — your optimism may drive some real successes here and there, and we’re hesitant to pop the bubble, but really it’s a lot worse than you even realize, and most of the things you’re supporting are doomed. We would like to convince you to face the facts, and stop optimistically doing the not-actually-adequate Patreon / Liberapay thing. Instead, we need to build a new social contract to figure out how to get all those sympathetic folks who are not us activist / donating insiders and bring them on board. And they may mean something like a strike. We STOP being suckers clearing the road on our own…

And this is a lot like your threshold model except… we don’t go on strike and say “we’re doing no work until our demand for X is met”. Instead, we’re saying “we’re doing a work slow-down and going to invite more of you to help, and we’ll not only get back to where we were but are up for going a lot farther if we get far more of you bystanders to join in”.

My core point is: Maybe this is part of why you feel uncomfortable (we’re, in crowdmatching, potentially discouraging the suckers who are already doing something), and that this is backwards. And yet it’s still the right way to build the movement we need long-term. You’re not the first person who expressed this discomfort (or if I’m guessing wrong, I can tell you others do feel this way), but it comes nearly exclusively from the sort of people who are really active and engaged already and are inclined to invest the sort of serious time that you and I have put into this conversation. The sort of people who insist (but are wrong) that people want to donate all they can (I know that isn’t you though).

From the people who are not donating or volunteering or even hopeful today (and I was once one of those incidentally), crowdmatching can feel like a real fresh hope in a way that threshold systems do not (but now that I understand your proposal better, I do think it’s a real improvement over existing threshold models, at least for some projects).

If the road is blocked I cannot freeride.

It’s not black-and-white. A road can be semi-clear, enough to struggle through slowly.

In funding terms, either there is enough money for someone to put in actual paid hours on the project, or there isn’t.

Yes and no. When this is true, a minimum threshold makes sense. It’s often not true. It may be someone volunteering and losing money on hosting costs, and they will be able to keep going better if we at least cover those costs better. It may be a freelancer who has to take on more or less proprietary clients depending on how much funding their FLO project has. Or it may be a team on a big FLO project who are thinking about whether or not they can fund some extra training or travel to conferences… For many (most?) FLO projects, it’s not all-or-nothing in terms of the value of income.

On tipping, I agree with everything you said, with one caveat: small income from some crowdmatching patrons still has the effect of “these people support me at least”. And anyway, we’re not stopping anyone from also tipping outside of crowdmatching.

In prec-shold the minimum and the maximum is the same level.

[my original thought while reading:] Can you come up with any real-world example where this is a good fit? Nearly all the FLO public goods I can think of do not work this way. Any that even have a minimum that makes sense also could greatly benefit from income beyond that and would not have any desire to cap that. And they’d be extremely hesitant to refuse valuable income that was less than what a true maximum cap would be. And self-donating as the only means to break the levels apart feels like an awkward hack, even if it’s publicly acknowledged.

[addendum after finishing:] I’m still skeptical somewhat (the author could still grow significantly, hire a better editor, illustrator, promoter, maybe expand into film adaptations… etc), but I accept that many niche projects (including many who have come to us and we knew were not a great fit) really would be appropriate for your model.

This is not an appealing pitch to me.

Sorry for the confusion, that wasn’t the pitch itself, it was my description of the pitch. The pitch itself is more like “so, instead of donating on your own, you make a pledge: I’ll donate a tiny bit for each other patron who gives with me!” and consistently, most people feel good about this and intuitively see how it could work well.

It’s all about not wanting to be a sucker.

Let me put it my way (which probably means a tweak to the game in the game theory): If I could be the sucker who completely transforms the world for the better, I’m okay with that. I actually want the result, first and foremost.

It’s not about avoiding being a sucker as the priority or as freeriding as the priority. It’s about avoiding the WORST case scenario: being a sucker with big costs and nothing in the world really changes, no good result even comes of it.

If I donate $5,000 to Inkscape, it won’t go that far, but it will be a HUGE burden for me. I take solace in the idea that working on Snowdrift.coop has been an interesting learning experience etc. etc. but it’s still not worth it if we don’t succeed at making real value in the end.

The worry is that I could shovel a TON of snow and still have more snow fall than I can shovel, so it’s all a total loss. But let’s consider a situation where there are already enough other suckers shoveling that it’s sorta working. It’s a job for 20-50 volunteers working really hard or for 10 full-time, well-funded paid folks, say. There’s fluctuating 18-25 volunteers, so it’s ups and downs but sorta working. Should I join the volunteers? It seems like a huge burden with very uncertain results, and some risk of others burning out etc. I can’t afford to pay a single full-time person on my own. Should I donate to a threshold campaign to add 1 full-time person? Maybe… still seems like a big personal burden for a questionable nothing-really-changes in the big picture…

What I want is a vision of how to get 50 great volunteers and 50 backup ones or get the full 10 paid folks (and, I want the hope that if we get there we push forward to expand the project and really take on the proprietary competition even harder!). But that’s such a fantasy. If anything I do (even clicking “pledge”) is nothing, just marked “failure” short of reaching the dream, then it’s not even worth it. I want to tell others that I’m in on my part of reaching the dream if there truly are enough others to help, and if we get half-way there and at less burden to me than getting all the way there, that’s still positive. And I’m willing even to come volunteer if the understanding is that I’m not going to take sucker-level burden with nothing else changing.

My willingness to contribute isn’t black-and-white / all-or-nothing. And it’s somewhat proportional to how great I see the outcome being.

please don’t mix in crowdmatching with precise-threshold

We won’t. But we’ve had notes forever about “what happens if we reach full funding” and one of them includes the run-in-reverse (refund), i.e. allow new pledges and just divide the total among everyone so that new patrons reduce the burden for others. That’s not something we got from you.The only reason it’s not currently on the limits page (it might have been in the past, not sure) is because we’re doubtful that it really makes sense.

This has usually come up when someone asks, “I give more when more donors join, that seems backwards, I thought I’d be able to give less when others join” and our answer has always been, “well, that would only make sense if the project was fully-funded. We’re focusing on getting to fully-funded in the first place!”. I’ve had nearly that exact exchange a number of times.

Whether we add a minimum “funding is off until it hits X” (likely to be an option) or a “fully-funded, spread the burden” maximum (doubtful, again, hoping to get to where this is even worth considering), it won’t be because you brought up your precise-threshold model or an attempt to combine them per se.

The more people join in as patrons on a crowdmatching project, the heavier everyone’s burden becomes.

I think this is reiteration but: that claim is not true relative to the result! As co-founder David emphasizes, if you’re okay with being 1 of 1,000 patrons putting in $1, then by being willing to put in an extra $0.001 when the next patron joins is comparable to being matched 1,000 times over (and so on)! Your burden goes up a fraction of a cent, but the project gets $2 more funding. Or if we scaled this to other numbers… the point is: in crowdmatching, your burden goes up MUCH slower than your increased BENEFIT from the funding improvements for the project. Your relative burden is being constantly REDUCED, not increased.

It’s like if we were all cleaning up litter in the neighborhood. You agree to pick up an extra piece of litter for each volunteer who joins the litter brigade. This isn’t a bad deal with a heavier burden. This is like “YAY, I just pick up one more piece of litter to getting 500 pieces removed from my neighborhood, thanks to the new volunteer!” That benefit is absolutely worth the miniscule extra burden. This is perfectly fine game-theory.

Please don’t confuse what’s punishing for projects (the biker) with what’s punishing patrons (the donators) if the goal is to get many patrons.

It works the same way the other way. The patrons are happier when the bicyclist goes the extra mile. They like that they give extra $, knowing that the other patrons are also and together (and due to the social signals of the bicyclists effort), they are doing that much more for the cause. Nobody is punished here — because we’re talking about a case where more funding directly means greater results from the project/cause. The punishment framing only applies in cases where there’s no further returns beyond the threshold.

A threshold system is designed to ease your mind. Crowdmatching lacks that.

You mean in terms of risk? Crowdmatching is different, but it’s still true that my risk is low, much lower than plain unilateral donations with no matching or threshold.

gaming the system as one of the strongest arguments against threshold pledge systems when your own proposal is much more sensitive to the same flaw.

Thanks, I’ll fix that. It’s a good point. The actual reason we put that in, however, was not to say that gaming itself was fatal. The point was to illustrate how arbitrary the thresholds often are. If a threshold at Kickstarter was always the actual minimum needed to go ahead, then the gaming would never be rational. It only ever happens because the thresholds are so arbitrary / badly set etc. and so people game when they change their mind and realize they’d be okay with a lower threshold.

This gets at, I think, our core difference of viewpoint. Your focus is on projects with a clear threshold, they need X and no more. Less is no good, more does little good. They need that amount. Our focus is on projects that have no such point clear at all.

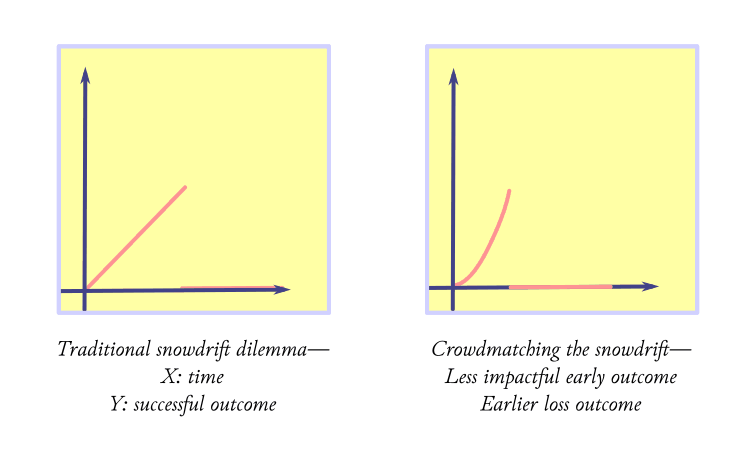

Consider the snowdrift game. You’re viewing it as yes or no: is the road cleared? We’re viewing it more as a continuum from more blocked to more clear. Furthermore, we’re focused on the broader question of maintaining the road and keeping it clear iteratively, ongoing maintenance. Finally, FLO public goods aren’t all like the prototypical snowdrift case, though they all have aspects of the dilemma.

Increasing the burden of my fellow individual patrons a la crowdmatching is demotivating to me personally.

Aha! This is a core insight. It’s personal, social, emotional… not part of game-theory math. At first I guessed you just personally didn’t like this way of negotiating cooperation. And in this, you’d be in a minority but not the first I’ve heard. But I now think this is amplified by the framing you have of thinking of the type of project best-fit for threshold approach, so it’s that along with some other personal feelings.

I described above my characterization about cultural context. If you are mostly concerned about reducing the burden on everyday citizens and getting corporations and the wealthy to do their part (I’m sympathetic), crowdmatching is backward. But for me, I’m thinking about how to get people to move their funding to public goods and away from the wealthy corporations…

So, I’m not thinking of crowdmatching as just increasing the burden of others. I think of it as moving other people’s money from Adobe to Inkscape, so to speak. It’s certainly not that simple. But the more we all work together to give Inkscape real major funding, more funding, not mild low-threshold funding, but outcompete-Adobe funding… the more we’re freeing everyone from Adobe and their influence and putting capital in the hands of FLO projects and citizens and not in the hands of the corporations. Our goal isn’t to burden people, it’s to move where they put their resources so that they are actually more freed.

Go with my litter example: all the volunteers picking up litter are the responsible citizens, not the litterers or the profiting producers of all the disposable waste and trash that shouldn’t have existed in the first place. Yeah, I’d rather McDonald’s be responsible for all the litter of their products or to figure out how to stop litterers entirely. But if we successfully clean up the neighborhood, yes on the backs of all of us innocent, burdened residents… then we have a clean neighborhood. We can also try the other things to pursue justice more broadly.

[Kickstarter] I’m not saying this is common behavior at all!…

Well, there’s mounds of evidence that threshold campaigns get almost all their pledges at the beginning and end. The early-adopters join right away, then everything slows down. At the end, maybe people step up to try to help push it over the top (or to buy the thing in a product-type scenario of a met-the-threshold). So, you might be pretty normal here.

“I won’t be putting in my best effort unless others are too. Others must suffer as much as I suffer.”

It’s more like a refusal to suffer a lot for a poor result. We can all enjoy an amazing result if we work together, and my motivation is proportional to how amazing the impact will be. Again: if I have a slightly higher burden but get an amazing Inkscape (and the results of economic shifts to public goods overall), I’m totally winning out. That’s not suffering.